If the candidate at the top of a party’s ballot ceases to be an asset to the other candidates, what do you do? Who decides to replace such a nominee? Missouri’s Democratic Party answered these questions in the 1932 Missouri Gubernatorial election, writing a new chapter in state electoral history.

The Incentive

Why does one seek election to representative office, and why do wealthy individuals and organizations contribute vast sums to such an aspiring public servant? The incentive is the spoils of office, the payoff is in the graft. Graft is a slang term for preying on the public, consisting of “advancing one’s position or wealth by dishonest or unfair means, as by utilizing the advantages of an official position for one’s gain” [emphasis in original].[1] While a certain amount of illegal graft occurs, the lion’s share occurs legally, as nationally syndicated columnist John T. Flynn notes:

Those who make the most money out of politics are, usually, those who hold no public office. Contractors, insurance brokers, lawyers, gamblers and such are able, through their official connections, to feather their nest handsomely, not necessarily by dishonest, but unfair means – unfair to the public.[2]

Today the list includes corporations, developers, nongovernmental organizations (NGO), academics, foundations, and most especially, a politician’s family and friends. By nature of their access to the officials who control vast sums of taxpayer money, they exercise an unfair advantage over the private citizen.

The Political Machine

The growth of urban areas with enclaves of ethnic or religious minorities gave rise to the political machine. As chairman of the Jackson County Democratic Party in Kansas City, Missouri, Thomas J. (Tom) Pendergast built the fastest-growing political machine in the country. By 1928, the Pendergast machine rivaled New York’s Tammany and Chicago’s Kelly-Nash machines. Lured by the substantial state budget which could benefit his Ready-Mixed Concrete Company, Pendergast nursed the ambition to place a man in the governor’s chair.

An aficionado of the Sport of Kings, Boss Tom knew how to pick a winner, betting on Francis Wilson in 1928. A thoroughbred from a winning bloodline, Wilson made a good showing in the gubernatorial race, and spent the next four years priming to fulfill his lifelong dream to become governor of the “great commonwealth of Missouri.”[3]

The Democratic Primary

A savvy campaigner, Wilson refused to debate his Democratic primary opponent, Russell Dearmont, head-to-head. “I’m too old… [to be] trapped by a scheme to set me on the platform alongside that handsome young opponent of mine,” quipped Wilson, preferring to “stick to the issues,” without the hassle of an opposing argument.[4] Avoiding direct attacks on Wilson, the dark horse Dearmont mounted an anti-Pendergast, anti-bossism campaign, but the insinuation was clear. Wilson nosed-out Dearmont in a neck-and-neck sprint for the nomination in August, making him the odds-on favorite to sweep the state ticket into power.

Before the gavel closed the state convention, loyal Democrat-affiliated newspapers joined Republican-friendly broadsheets in sounding the klaxons regarding Pendergast’s efforts to gain state control. Wilson, a veteran politician who prided himself on a folksy, neighborly appeal, chafed at allusions to “Pendergast’s pony.”[5]

Wilson Falters, Enters General Election From His Basement

In the final days of August, Wilson suffered a back injury while attempting to enter a taxicab. The torn and strained muscles were painful, according to Wilson, but the injury was not deemed serious. Yet, rather than mount the campaign stump in the home stretch, the candidate remained at home for weeks. Does this sound logical for an old mudder politician known for “pressing the flesh,” preferring chatting with greasy-spoon patrons over mass appeal rallies?

With one final race to run, Wilson was still in the paddock as his opponent entered the starting gate. The GOP nominated sitting Lieutenant Governor Edward Winter, a young, erudite, on-the-bit newspaper editor and publisher. Winter burst from the gate, setting the pace on the themes of economy in government and anti-bossism, blanketing the state with literature quoting arguments from the campaign speeches of Wilson’s Democratic challenger Dearmont.[6]

A Threat to The Democracy

For two weeks, Winter’s verbal bombardments went unopposed, inflicting serious damage statewide, even in Democratic strongholds. Bear in mind, at the top of the ticket, Wilson was the standard-bearer, the pacesetter of The Democracy[7] in Missouri. Party and machine officials openly worried Wilson’s inactivity jeopardized the down-ballot races, although no one stood to lose more in this winner-takes-all gamble than Boss Pendergast. As the implicit power behind the entire Missouri Democratic ticket, election defeat meant the end of his reign of power, forever.

Was this Wilson’s desire? Did he suddenly realize the threat that Pendergast posed to, not just himself, but the entire state? Was he willing to sacrifice his personal dream for the good of his fellow Missourians? If so, did he think that Boss Tom would sit idly by and allow it to happen?

The Unexpected

The deadline for changes to the November ballot, October 19, loomed large. With rumors abounding, on October 11 candidate Wilson, feeling fully recovered, announced plans to hit the hustings the next day in a Kansas City suburb. His assistant persuaded him to remain at home that evening to finalize campaign preparations, retiring for the evening in fine spirits. By 9:00 the next morning, the Democratic front-runner was dead. Wilson was buried before an autopsy could be performed.

Suddenly Pendergast’s race to state domination stopped dead in its tracks. The anti-Pendergast forces in the party unexpectedly had a golden opportunity to unite behind any number of young, rising candidates in their stable, effectively blocking a machine-chosen replacement.

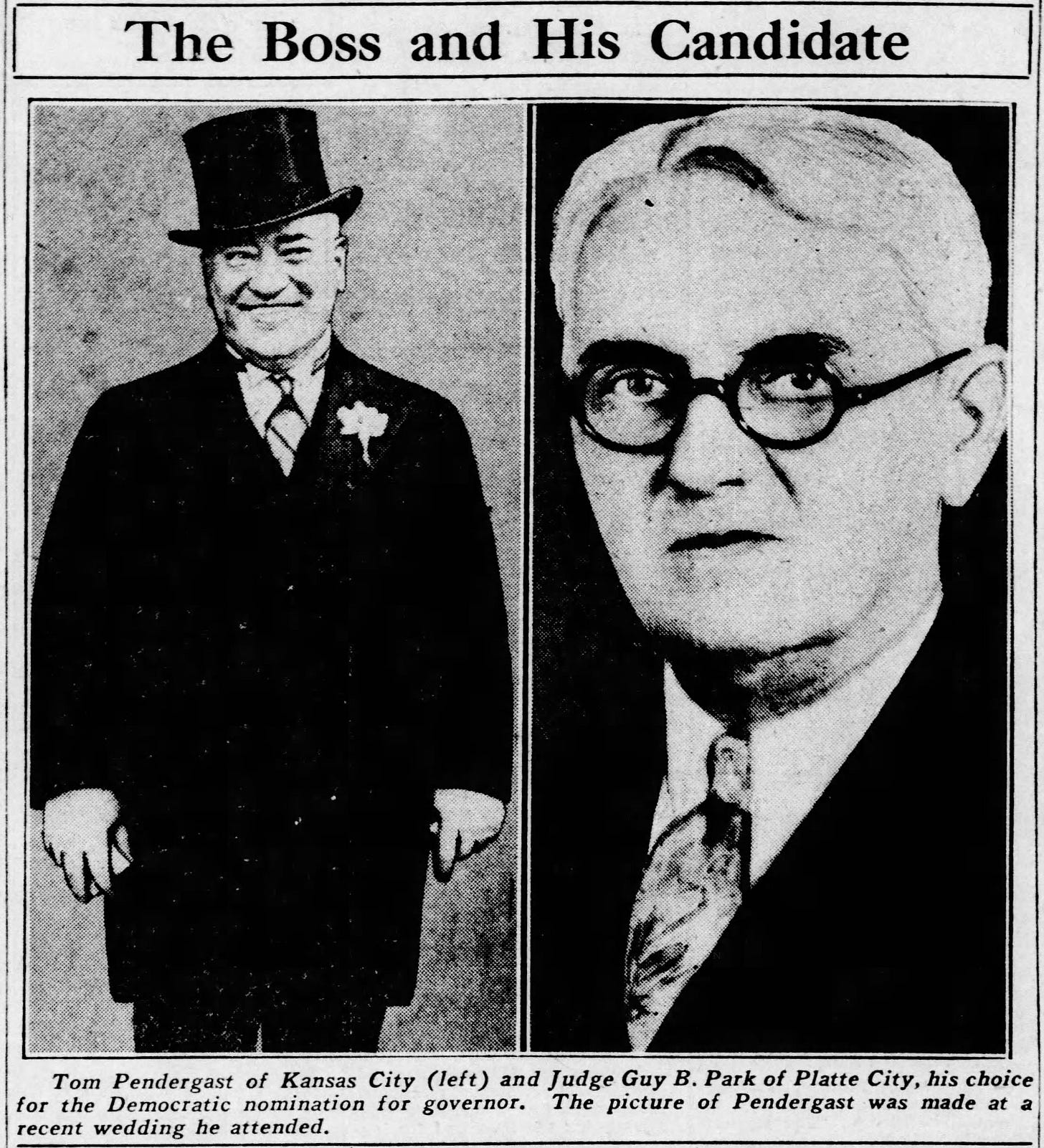

The Boss and His Candidate

Hardly had Wilson been declared dead before Pendergast put forward his closer – Circuit Judge Guy B. Park. The only male to ever graduate from the all-girls Gaylord Institute (his mother was principal), Park had the magnetism of a snail race. Vainly did leaders from outside of Kansas City oppose Park’s selection, fearing backlash from voters resentful of replacing a thoroughbred with a jackass.

The Kansas City Journal, a pro-Democratic daily, warned:

Judge Park would be subject to vitriolic attack from the Republicans. The Republican orators would go up and down the state pointing out that Judge Park has sat on the circuit bench in Platte county while a gambling house operated openly in the county and a race track was operated in violation of existing state laws…The plain facts are that he has been judge of the circuit court and thus in control of impaneling the grand juries…No grand jury has ever taken cognizance of the Green Hills club, where gambling has been open, or the Riverside track, where there has been no secret about betting on horse races. Why endanger the chances of the party…[8]

An Unbelievable Victory

No serious gambler would bet on a long shot like Park, but Boss Tom told his political captains “nothing must be left undone to see that judge and the Jackson County machine are victorious”[9] on election day. Judge Guy Park embodied “bossism” and commercialized vice with a capital G for graft.

But Fate has a way of smiling on fools and sinners. Incredibly, in 10 days Park was able to woo the “show me” state voters, overcoming a polling deficit to win the Governor’s seat with a 300,000 vote margin over his GOP opponent.[10] Park the toady, limped over the finish line and single-handedly saved the Democracy and the Pendergast machine in 1932.

And one final thought, on the heels of his ascension to state power, Pendergast set his sights on putting a man in the White House. In 1934, he backed a failed haberdasher in a race for a seat in the US Senate. The longshot won, was eventually elected Vice President, and by another quirk of fate, became President of the United States - Harry S. Truman. Like I said, Pendergast had a nose for winners.

[1] John T. Flynn, The Roosevelt Myth (New York: Devin-Adair, 1948), 236.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “A Life Aim Unfulfilled,” Kansas City Star, October 12, 1932.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Curtis to Make 3 Talks in State,” Moberly Monitor-Index and Evening Democrat, October 3, 1932.

[6] “Caufield to the Stump,” Kansas City Times, October 3, 1932.

[7] Since the days of Andrew Jackson, the terms Democratic Party and The/Our Democracy have been used interchangeably.

[8] “Judge Park Unavailable,” Kansas City Journal, October 14, 1932.

[9] “The Boss and His Candidate,” St. Louis Star and Times, October 15, 1932.

[10] Guy Brasfield Park Papers, 1932-1937, State Historical Society of Missouri.

My, how history repeats itself.